Why I Sent 365 Poetry Submissions in a Year (and What I Learned)

At some point this year, I realized I was doing that thing a lot of writers do: hoarding poems on my hard drive and Apple notes and quietly torturing myself about whether they were “good enough” without actually letting anyone see them.

I was writing a lot. I was revising a lot. Then I started showing my close friends and that helped me gain a little confidence. When I started submitting my poetry in May 2025, I was grieving, anxious, and checking Submittable way too often. My earliest rejection I tracked in in Duotrope is dated May 27. I remember how my heart dropped when I received it. I thought, I cannot live like this, glued to my inbox, refreshing and waiting and letting every “no” sting me. I was worried it would be death by a thousand cuts.

So I gave myself a challenge to send 365 submissions for the year. I thought to myself:

What if I sent out so much work that rejection became normal?

What if I collected so many data points that “yes” and “no” were just information; a collection of 1s and 0s?

That’s where the idea of 365 poetry submissions over 365 days came from.

How It Started

When I first had the idea of doing 365 submissions in one year, I knew I needed some more information to make sure this was an achievable and realistic goal. So, I did some googling and found this amazing post on little infinite from Lisa Marie Basille about setting rejection goals.

The evaluator in me leapt for joy.

Not only would it be possible to average a submission a day, but maybe it was even the right way to frame submissions in general. To take it even further, maybe it wasn’t 365 submissions I should focus on, but 365 rejections (or at least 100 rejections according to Kim Liao linked here on Literary Hub.)

I didn’t begin this on January 1 with a perfect plan and color-coded system (and you don’t need to either—read on!). I started in May, after a few early rejections, when I realized I couldn’t keep tying my mood to one inbox notification at a time.

If we’re being specific and technical, I only needed around 225 submissions between May and December to match the “one per day” average for the remaining time in the calendar year.

But honestly, the number wasn’t really the point, not even at the start.

I kept the goal at 365 because it felt big enough to force a real shift in how I was approaching the work. Even though I knew it would be difficult, nearly doubling my daily average of submissions I would need to succeed if I had started in January, I wanted to challenge myself to do 365 in a year. Plus, it’s catchier.

The first phase strategy was very simple:

Write &: I wrote intensely in the spring, more intensely than I’d ever written before, partly to survive what was happening in my life.

Submit: Any time I learned about a new journal or a new call, I sent what I thought was a good fit.

My Best: I sent my best poem to places like The New Yorker and AGNI because… why not? Someone has to be in the slush pile. Why not me?

It wasn’t a polished “poetry submission strategy.”

It was more like: write, send, repeat.

How My Submission Strategy Evolved

The real strategy and structure came later—after I’d been in motion for a while.

Once I had a decent number of submissions out, I started to lean into my evaluator brain:

I began tracking which journals felt like a stretch vs. a good match.

I signed up for Duotrope in June not just for deadlines but to understand acceptance rates and submission patterns.

I learned that in poetry, a 20% acceptance rate is not actually “elite.”

The truly competitive journals operate in the low single digits. Since I was new to submitting my work widely and do not have an MFA, this was of shocking to me.

This is why it is so important to have context when we’re talking about numbers and benchmarks (which of course I tell my clients in evaluation all the time, but the poet version of myself forgot to listen).

I looked at which journals have Best American Poetry or Pushcart wins not just nominations.

Once a poem started performing well—personal rejections, finalists, longlisted—I got a bit more picky and only sent it to journals I considered equal or higher tier than where it had already been so it could (hopefully, ambitiously) settle at the highest rated publication possible.

My process wasn’t perfect. (It still isn’t!)

I didn’t follow a rigid or elegant system. (I still don’t!)

Instead, I wrote, submitted in waves, made mistakes, learned how acceptance rates actually work, and slowly moved my best poems toward harder journals. It felt messy sometimes, but soon, it also started to feel genuinely strategic.

I also made some choices I wouldn’t repeat—like spending money on chapbook and full-length contests before I’d even placed individual poems. Live and learn! At the time, I was writing so much about one topic (grief) that it felt like since I technically had enough pages written to fill a full length manuscript, didn’t mean I had something ready to submit or publish as a manuscript.

In hindsight, I should have waited a bit longer and let the poems prove themselves first.

If you’re in the same boat as me, I hope you’ll have a bit more patience with yourself or learn that now-kind-of-obvious lesson that I learned a bit too late and wait a smidge before submitting chapbooks or full lengths.

The Rules I Eventually Gave Myself

These “rules” are where I’ve settled (for the most part). The rules weren’t all there on day one, but this is what the framework looked like once it solidified:

1. Send the strongest version of each poem you have that day.

Not the fantasy version you’ll write in two years—the best you can offer right now.

2. Aim for a mix of stretch and match journals.

A realistic poetry submission strategy includes both the dream journals and the steady, well-edited ones that genuinely fit your work. But don’t be afraid to submit to the highest most difficult places and a couple you just vibe with.

3. Track everything in one spreadsheet.

Luckily, I did this from the start, but my spreadsheet soon became unwieldy an a pain to update (even for me, and I do this for a living). All you really need are the following columns: Title, journal, date sent, decision, decision date, and notes. Nothing fancy. Or better yet, skip all that and use Duotrope like me.

4. Don’t let a rejection strand a poem.

If a poem comes back and still feels like one of your best, send it somewhere new as soon as you can. Don’t let it sit in limbo. Or better yet, submit all your work simultaneously (unless it’s at The New Yorker), as long as you are sending it to the most ambitious markets on your publication short list.

By the time this rhythm was in place, I wasn’t thinking about the goal anymore. I was thinking about the work.

What Actually Happened

The original expectation was simple: tons of rejections.

And, that is what happened! To date I’ve received 484 rejections from 158 different publications, journals, magazines, contests… you name it, I’ve been rejected by it!

I wanted to get to a place where “no” landed so often, with such regularity, that it stopped having power over me and my time.

But once I started sending work consistently, some other interesting things happened:

Within the first few dozen submissions, I got my first acceptance.

Then another!

Then a handful of finalist, longlist, or “this was close” notes from journals I respected.

I also started receiving personal rejections from editors who took a moment to say something encouraging—which turned out to be its own kind of win.

Speaking of wins…

The Wins

One of the first acceptances that really moved me, that I felt deeply, was Pine Hills Review, which accepted my long, three-part, personal poem Claire’s 1997, 2003, 2025 for their Mall feature. Up until then, most of my acceptances had been for very short pieces (two haiku, two haibun, and one grouped string of haiku).

When I found out I was being published in the feature, I felt like Pine Hills had essentially said: this big, layered, ambitious, central poem has a home with us. At least, that’s how it felt to me. When it went live, I took a screenshot and send it to my friends. I still get a little verklempt thinking about it.

And after Claire’s was accepted, something changed in how I understood my own voice and my place in the literary world. I know we shouldn’t pick favorites, but I will never forget that.

Most recently, one of those poems I submitted way back in May, won a national prize—the Bellevue Literary Review’s John & Eileen Allman Prize for Poetry. I’ve written a whole blog post (or two) about what it felt like to win this award, especially winning for a poem about my father’s death. But when I learned I was a finalist, it felt like an outcome of being fully inside the process for months: writing, revising, submitting, tracking, adjusting, learning. And winning!

The Losses

Yes, I am honored and grateful to have these poems published. It feels like winning the lottery.

Do you know how many publications rejected me before I learned I was a finalist for the prize?

134

That’s right, one-hundred and thirty-four different markets rejected the entirety of the packet I crafted especially for them with a unique twist on a cover letter every time.

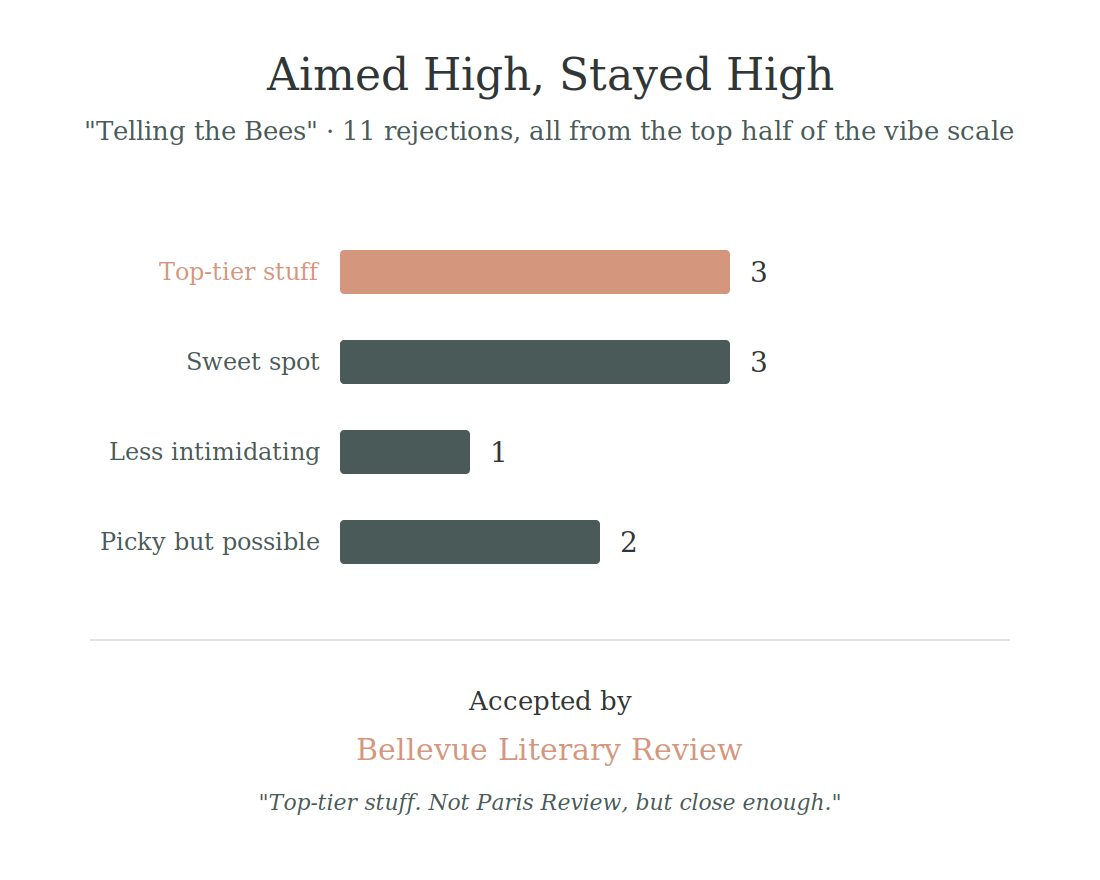

Do you know how many publications passed on my BLR winning poem Telling the Bees?

11

ELEVEN!

And these weren’t boutique, fledgling, pay-to-play publications. Most of them ranged somewhere between tier 1.0 and tier 1.5 on my personal scale. But don’t take my word for it. Well… do take my word for it, but check out the evidence below using Chill Sub’s 10 point vibe scale.

This is a top-tier-heavy strategy.

All 11 rejections came from the upper half of Chill Sub’s vibe scale, and the poem was accepted exactly where it was aimed. This approach—patient, selective, unflinching—treated the work as strong until the right editor agreed.

It wasn’t overnight.

It wasn’t accidental.

It was accumulation.

What This Year Taught Me About the Work

A few things became very clear:

I revised harder because I knew editors were actually reading.

Once you see a poem almost break through, you start revising with new eyes.

I developed a real internal A-list.

Some poems consistently performed well—personal rejections, finalist notes, editors remembering them and encouraging me. Those became my guideposts—how I knew I was on the right track.

This list is just for me. Right now it’s about 30 poems, with 12 that I think have a real chance at landing at one of those top-tier publications.

I learned the difference between “good poem” and “good poem for this journal.”

Some publications love voice and risk.

Some love quiet domesticity.

Neither is better—but they’re not interchangeable. Submitting this often to a wide variety of publication helped me understand where my poems fit and how I would describe my own voice and style.

I remembered, even as a poet, to treat data as information, not judgment.

You’d think I’d easily be able to tell myself this after 15+ years as a professional data analyst and evaluator, but we are always our own worst clients, aren’t we?

Every acceptance or rejection became a datapoint about one poem at one journal in one moment in a much larger picture of my presence in the literary world. I realized rejection is not a verdict on me or the work.

It may seem almost paradoxical, but thinking this way helped me combat the imposter syndrome I was feeling because I did not go to school for creative writing (I went for Behavioral Science and Public Policy).

What I’d Do Differently

If I hit reset, here’s what I’d change:

I’d be more patient about contests.

I’d learn the landscape earlier instead of assuming I understood prestige based on which publications I’d heard of or my assumptions about reputation.

I’d trust my evolving instincts more.

I’d be more strategic from the start and adapt my thinking and approach as I learned.

But, the process was never about being perfect. It was about learning and growing around my grief. Plus, perfection doesn’t exist.

Advice If You’re Considering a Submissions Challenge

You didn’t ask for my advice, but if you’ve read this far, I hope you’re ready for it:

1. Pick a number that stretches you but doesn’t break you.

It doesn’t have to be 365. It could be 50 or 100 or 150. Think about setting a SMART goal (I can’t help myself) to push yourself, but also be honest and kind with yourself if things need to adjust along the way. You’re a human, not a machine.

2. Keep your tracking simple.

The days I (in hindsight) wasted trying to create the perfect spreadsheet, the perfect formula, the perfect code… Oy vey. Don’t let the spreadsheet become the art, even if you’re an Excel wizard like me. Maybe especially then.

3. Decide in advance what rejection means.

As the New York State Lottery says, if you don’t play, you can’t win.

And if you do play the submissions challenge, every outcome—yes or no—is just information, which in the work of poetry publishing, is a win in itself. Rejection doesn’t make your writing good or bad. It tells you what one editor thought about one poem at one moment.

4. Pay attention to personal rejections.

They are gifts. Truly.

No one has to send you a personal rejection. And if we want to get real about it, no one has to send you a rejection at all, the minimum they have to do is just not print your work.

It is more work than to give you a personal rejection and the sender can’t know how it will be received, so there’s a little bit of risk involved as well.

It is easier for publishers to hit a button that automatically fills in your information into a tidy email. Personalized rejections show where your work is almost landing. So take the time to find the diamond in the rough; the piece of feedback that you agree with and can implement in every personal rejection you receive. Find something you can use.

You could even seek out personal rejections.

I don’t know that this will increase your chances of getting a personal rejection, but here are some journals that have sent personal or thoughtful notes to me this year:

Smartish Pace

Dishsoap

Book of Matches

Neon & Smoke

Lake Effect

MacQueen’s Quinterly

wildscape

Pine Hills Review

Passionfruit Review

Sky Island Journal

LEON Literary Review

American Poetry Journal

Overgrowth Press

Gyroscope Review

(Not guarantees—just some data on editors who are reading with intention.)

5. Keep writing at the center.

Submitting is part of the work. But writing is the work. Write! Programs like Tupelo Press’s 30/30 helped me loosen the grip of perfectionism by sending drafts out into the world that I had written only the day before. I highly recommend signing up!

Where I Am Now

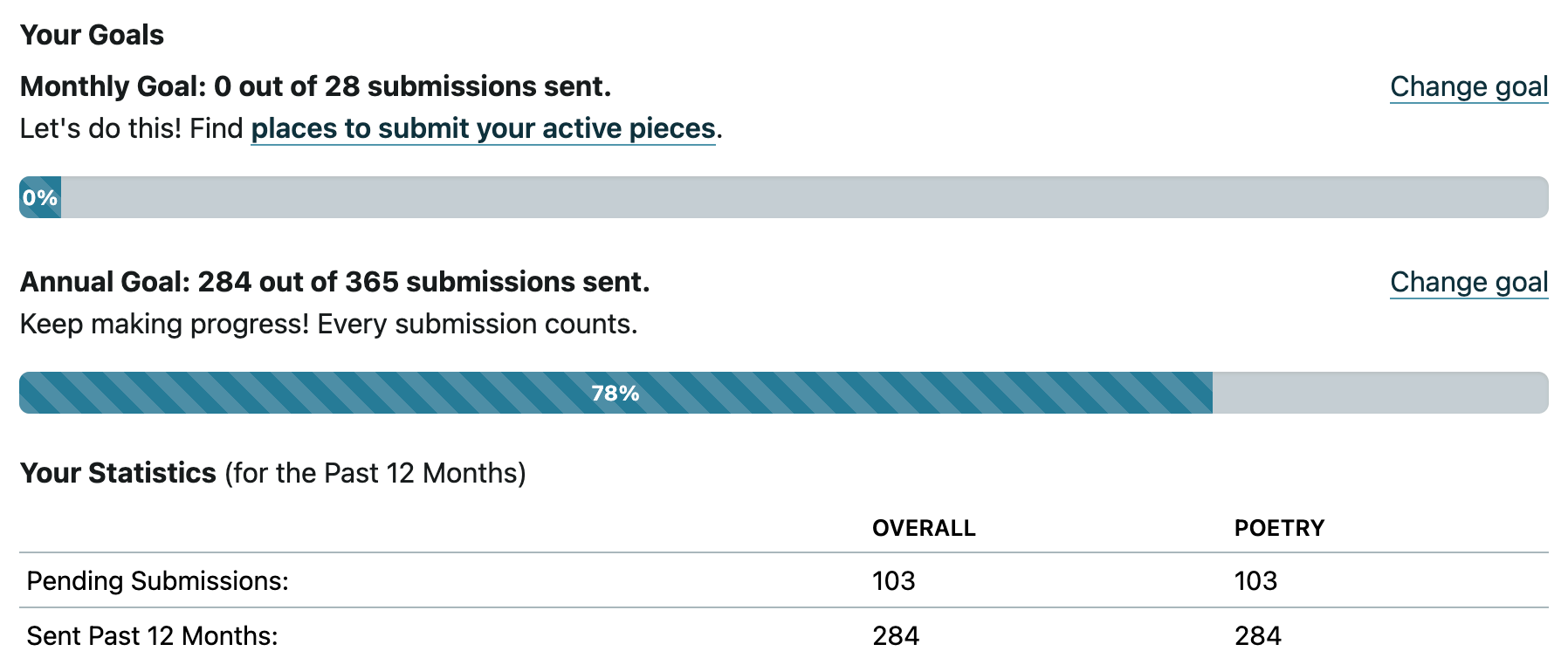

As I’m writing this today, my Duotrope dashboard shows 280+ submissions in the past 12 months. (see photo below)

My most recent rejection?

It came today bright and early this morning!

The rejection came from a dream journal I first submitted to when this whole process began back in May. That felt strangely full-circle and, honestly, motivating. Those poems are free now. They can go somewhere else and hopefully find a happy home with an editor and an audience that will be moved by them.

My most recent submission?

My last submission was yesterday. Actually, it was three submissions in one day: two contests and one general submission. One of each from Chill Sub’s vibe categories (on a 10-point scale, 1 being the most challenging):

Top-tier stuff. Not Paris Review, but close enough (level 2)

Living their best life in the sweet spot (level 3)

Send us your best but less intimidating (level 4)

Now what?

I’m still writing, revising, learning what “baked enough” truly feels like for my work, and thinking about what it takes to actually put together a chapbook and where the heck I should send it.

The rest has been and continues to be trial, error, revisions, and attention.

I didn’t become fearless.

But I did become more resilient, more informed, and more willing to take risks and stay in the game.

And for me, that’s the real win. That’s the reason I set this goal. So although I’m not stopping: mission accomplished!

Thanks for reading!

Dara Laine